Ever wonder what the f*ck is wrong with our economy? Why it seems like it doesn’t work for anyone? Well, it’s all the fault of Ronald Reagan and his goons! They started Neoliberalism and lied to the American people! Boooooo!

In the second part of this deep dive into the cornerstone of our economic thinking, we are going to actually talk about Market Fundamentalism, I promise.

Last time, we talked about Liberalism, its successor, Neoliberalism, and how both ideologies produced policies that lead to the disaster that is our present economy. To recall, here is the thesis of these posts:

Neoliberalism uses market fundamentalism as a bludgeon to push through harmful policies that disregard its effects on everyday people to the point that it has steered us towards the disaster of climate change.

What does all this mean? Why does all this matter? How does this relate to a changing climate? Why so many questions??

It will all be revealed, just keep reading!

What are Markets, Again?

Okay, so last time we talked a lot about the free market so let me give a little refresher. Using the supply and demand model, a free market is a system of exchange between buyers and sellers where the freedom of choice of either party drives the price to an equilibrium price (typically thought to be the lowest).

A free market is only a theoretical concept, since there are always rules that govern interactions, even in the most primitive settings. As capitalism became the dominant form of economic trade, markets started to form around important resources, known as sectors (or industries). These sectors started to require certain rules, depending on the nature of the resource.

Let’s go over some examples of markets and the behavior of sellers.

Example 1: Textiles

Once textiles started to become a resource, the supply chain started to generate its own requirements for labor, production, and sale. Labor was required to farm plant fibers. Fibers had to be spun into yarn. Spools of yarn were then processed to be strengthened and lengthened. Yarn was woven into fabrics. Large pieces of fabric were cut into various forms of textiles like towels, shirts, pants, etc. The finished products then had to be transported to a store or stand to be sold.

As time went on, efficiencies were discovered to increase yield, form better clothes, quicken production, and expand product choices. These efficiencies act as our first case of rules that govern markets. Of course, these rules are set by those running the sector, but they still affected the way each sector was run.

If there was a marketplace where there were two competing clothing companies, both would have to engage in these rules if they wanted to ensure that they were making comparable profits.

Additionally, these rules also added to the quality a consumer could expect. If one seller, call him S1, treated his fibers with a specific chemical treatment to strengthen the fibers, making them last longer, then the time between purchases would be longer, but the extra chemical would add to the cost of the textile. If the price, P, of the textile was a simple addition between labor costs (L), treatment (Trt), transport(Tr), raw materials (RM), and production (Pro), it would look something like this:

PS1=L+Trt+Tr+RM+Pro

If the second seller, S2, had comparable costs for labor, transport, raw materials, and production, but excluded the treatment then his price would be:

PS2=L+Tr+RM+Pro

Of course, that would mean PS1 > PS2 , since PS1 = PS2+Trt .

Therefore, a buyer would be saving money if he bought from S2.

However, a smart buyer would be able to recognize that the treatment that S1 applies to their product would increase the lifetime of the textile, LT. Since the treatment strengthens the fibers, it would act to multiply the LT by some factor we will denote as t. Since S1 and S2 use similar raw materials,

LTS1=t * LTS2

If the LT of S2’s product is 6 months, and the treatment extends the lifetime by 3 times it would be without, then the LT of S1’s textile would be 18 months.

In a two-year period, a buyer would have to pay for four units of S2’s product, taking his total cost to 4*PS2. Meanwhile, buying from S1 would only cost 2*PS1, or

2*PS1 = 2 (PS2+Trt) = 2*PS2 + 2*Trt

With this, as long as the cost for the treatment is less than the cost of S2’s textile then, over time, it would be better to buy S1’s textile from a consumer perspective, since you’re getting more bang for your buck. For S2, having the cheaper textile meant they sold 4 units in the time it took S1 to sell 2, giving them more profits in the long run.

Of course, I just made all of these numbers up, but it demonstrates the point well: Investing in better products will cost consumers less over time, but having a cheaper option will lead to higher profits. (no more math, I swear!)

Example 2: Planned Obsolescence

During the early 20th century, the top lightbulb manufacturers in the US and Europe banded together and formed the Phoebus Cartel. This cartel made an oligopoly, a market that was taken over by a few massive corporations and had enough power in the sector to set their own standards.

They decided to set the standard lifetime of incandescent lightbulbs to be 1,000 hours, instead of the 2,500 hours that was gaining in popularity. If we only use lightbulbs for about 8 hours per day (3 hours in the morning, 5 hours at night), that’s 125 days versus 312 days before replacement.

They realized if they started to make lightbulbs that lasted longer, then they wouldn’t be able to sell as many. If consumers only needed lightbulbs about once per year, instead of three times, they wouldn’t sell as many lightbulbs.

Additionally, if only one manufacturer decided to take the hit and make lightbulbs that lasted one year, that would also reduce the rest of the companies’ profits, since fewer people would need bulbs. For the sake of their company, each member of this cartel agreed to cut their lightbulbs’ lifetimes down to 1,000 hours.

At the time, they cited that lightbulbs with longer lifetimes produce less light (lumens per watt) as the reason for this decision. A valid concern, sure, but completely eliminating the choice a consumer has between a short-life, (slightly) brighter bulb versus a long-life, (slightly) dimmer bulb does not sound free to me.

Since each corporation was a major player in the market, they had enough power to not only affect the market in their favor but inflict fines on other manufacturers that produced bulbs with longer lifetimes.

The cartel disbanded after the start of WWII, but the practice of producing products that are designed to break with less than average use, have shorter lifespans, or become undesirable/unfashionable has continued. Known today as Planned Obsolescence, it has crept its way into standard product design.

In the last example, the second seller deciding not to apply the chemical treatment the first seller did, is also a form of Planned Obsolescence since they are intentionally selling an inferior product with the hopes of increasing sales.

A newer development in Planned Obsolescence has been the yearly release of cell phones. Companies like Apple and Samsung have gotten into the habit of taking their cell phones, iPhone and Galaxy, making marginal improvements, and then re-releasing them the next year as the “new” model. This practice creates a guise of novelty and inclusivity for those silly enough to wait in line for practically the same phone they already have and pay a few hundred dollars more.

Putting the Mental in Market Fundamentalism

So far, we’ve learned some incredibly basic economics, and how corporations can use those basics to negatively impact consumers.

Now, let’s finally talk about the big scary term.

Market Fundamentalism is a dogmatic belief that unregulated, laissez-faire markets will solve economic and social problems.

This means that economists that support this belief insist that letting markets operate without any kind of regulation is the most efficient way to solve problems that arise in society.

Their argument stems from the idea that governmental regulation hinders the choices of capitalists and makes it difficult to turn a profit, reducing further economic growth.

Quick example: Carbon taxes are a proposed regulatory remedy for climate change as it would charge emitters a tax based on how much carbon they release, reducing the amount of profit the emitter might acquire.

The belief is a direct result of Neoliberal thinking, that preventing government intervention will lead to more economic prosperity.

When Superpowers Go M.A.D.

This idea was borne out of the Cold War and the Red Scare. Since the USSR had stringent laws which determined the outcome of their economy, instead of letting it play out by itself, the narrative of Communism versus Capitalism hinged on the degree to which governments interfered with their economies.

For communists, heavy interplay between the state and its markets was key to economic growth, as evidenced by their ability to industrialize during the Great Depression, when the rest of the world could barely make ends meet. Their state-controlled economy scared many capitalists, as there was no ability to make a profit as all materials, means of production, and revenue were owned by the state.

However, the collapse of the USSR in 1991 was seen as proof that communism was a failed ideology, and the capitalist boom that decade was proof that capitalism was the superior form of economics. Although true, economists at the time seemed to use the collapse as proof that regulated markets led to communism, and thus collapse.

(That being said, the collapse was more likely due to the deep corruption of Soviet officials, the growth of the second Soviet economy/black market, and decades of stagnation leading up to 1991. Also, a contributing factor was the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl, according to Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the USSR at the time of the collapse.)

Oh, Bill

Taking the fallen Soviet States as a hint to further free American markets, President Bill Clinton started a new economic venture during his presidency that had the effect of Neoliberalism, but the mask of an egalitarian Liberalism.

To do this, he instituted reforms like charter schools, community banking, and ‘Empowerment Zones’ to spur economic growth and revolutionize how Americans saw any problems distressing the system. Instead, his reforms lead to the creation of new markets which were immediately cornered by already-wealthy entrepreneurs that ‘innovated’ to both relieve social problems and turn a profit.

They certainly turned a profit, since the Clinton Administration fawned over the businessmen driving these changes as problem solvers when most of these solutions were simply bandaids over systemic issues.

Additionally, Clinton made an effort to showcase marginalized business owners, students of color, and hardworking, single mothers to valorize them. This worked to invert the detrimental narrative of Reagan’s ‘welfare queens’ leeching off of social programs as a way to decrease social spending.

However, this had a negative effect. By highlighting success stories, it gave a justification to shrink the welfare state. The same outcome Reagan wanted—to minimize social programs. Meanwhile, Clinton passed the 1994 Crime Bill, leading to massive discrepancies in White vs. Black sentencing, mass incarceration, and over-policing minority neighborhoods.

Regulation, Renegotiation, and Reprivatization

Okay, so Clinton…total Neoliberal, right?

Well, it gets worse!

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed by Clinton in 1992 as a law to eliminate tariffs between the US, Canada, and Mexico. Though it was a great idea on paper, this deal caused massive job losses as corporations moved their manufacturing to Mexico to reduce labor costs, wage losses for American workers, and increased inequality.

It also led to the unregulated industrialization of Mexican factories which increased pollution, aiding in climate change. Luckily—and I was surprised by this too—it was the Trump Administration’s renegotiation of NAFTA into the USMCA that allowed for (some) environmental protections, though it does not mention climate change.

Of all the tragic failings of this deal, the most significant is a provision that allowed for corporations to sue governments when their interests were misaligned with the host country’s laws. Essentially, it gives power to foreign companies to pursue legal action when their investments challenge public interest.

Though this provision never affected American citizens, there were a few cases that sided with the corporation and required governments to compensate.

Breaking the Glass-Steagall Ceiling

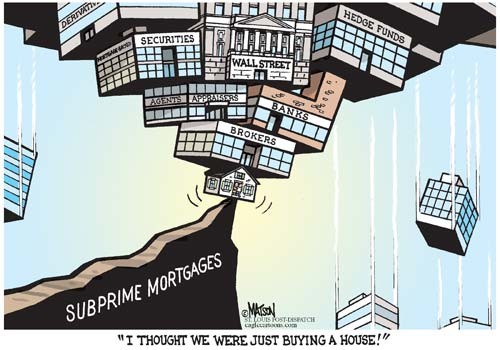

Another major Neoliberal policy was repealing the Glass-Steagall Act, banking legislation passed as part of the New Deal to separate investment banking from commercial banking. Since the Great Depression was partly caused by bankers making risky investments, FDR passed this law to ensure that there was a clear division between making financial decisions on behalf of account holders and making investments that may not pan out.

I argue that the repeal is the main cause of the 2008 Financial Crisis. The encouragement of average Americans to sign subprime mortgage loans lead to a $5 trillion real estate bubble bursting.

Following the 1999 repeal, the rejoining of the investment and commercial banking sectors meant that banks could gain more power and become conglomerates.

The biggest banks at the time, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and others, all leveraged massive amounts of money to encourage Americans to apply for housing loans. And since they had enough money to lose, banks agreed to sign mortgages from riskier and riskier lenders, increasing their overall financial portfolios.

That meant that when poorer lenders started missing payments (since they couldn’t afford the loans in the first place) the amount of money these banks actually had was significantly lower than what they reported.

The investments they made into the stock market, local startups, and other major corporations were in reality, void. Essentially, the checks these banks wrote as investments bounced all at once.

When consumers started to notice this, they would pull their money from their accounts, except, the money wasn’t there. Whatever money was left, went to the people in the know that got their money out first, leaving already poor Americans left holding the very empty bag.

These massive banks were saved though, (PHEW!) but it was by the same people who they left holding the bag, American taxpayers. The Federal Reserve cut massive checks to each of these banks to cover lost deposits, which the banks then promised to only the largest account holders.

Americans were left despondent, foreclosed on, and poorer than they were before.

Ending it Here!

Sheesh! This is already getting super long, and I’ve still barely talked about how this affects climate change… Gonna have to do a Part 3!

To conclude, I hope I have convinced you that the rise of market fundamentalism and the Neoliberal policies it influenced have had far-reaching consequences outside the initial goodwill they were signed with.

The freedom of markets can be a good thing, but without proper regulation, it can lead to a catastrophic event like the ’08 crisis. The continuation of deregulation through Neoliberal policies has no doubt been a net negative on American economics and has steered us all towards a dangerously unstable climate.

In Part 3, I will cover the actual environmental consequences of Market Fundamentalism and how we can start to reverse them. Most importantly, we are going to talk about how corporations were given constitutional rights, and, like Pinocchio, became a real boy and a real pain in the ass for Geppetto.

For my first dive into this topic, talking about how FDR saved us, and Reagan doomed us, click here.

When I finish, click here for part 3.